Sudanese police on Thursday fired tear gas to break up hundreds of protesters marching towards the presidential palace in Khartoum, as demonstrations demanding President Omar al-Bashir’s resignation spread to other cities and towns.

Protesters chanting “Freedom, peace, justice” had gathered in central Khartoum and began their march but riot police quickly confronted them with tear gas, witnesses told AFP.

People also took to the streets in the Red Sea city of Port Sudan, in the provincial town of Gadaref and in the agricultural hub of Atbara, where the first protests broke out on December 19 after the government tripled bread prices.

The protests have since escalated into broader demonstrations against Bashir’s three decades of iron-fisted rule that have triggered deadly clashes with the security forces.

Officials say at least 24 people have died, but human rights groups have given a higher toll.

Amnesty International said last week that more than 40 people had been killed and more than 1,000 arrested.

Human Rights Watch said the dead included children and medical staff.

After riot police broke up the march in downtown Khartoum, crowds of residents in the capital’s Buri district staged a new rally, witnesses said.

An image grab taken from AFP TV on January 17, 2019, shows a man suffering the effects of tear gas after protesters marched towards the presidential palace in Khartoum. By Linda ABI ASSI (AFP)

An image grab taken from AFP TV on January 17, 2019, shows a man suffering the effects of tear gas after protesters marched towards the presidential palace in Khartoum. By Linda ABI ASSI (AFP)Protesters pelted rocks at riot police who in turn fired tear gas.

Video footage showed some protesters wounded but they were treated by fellow demonstrators. It was not immediately clear what caused the wounds.

People also protested in Khartoum’s northern district of Bahri, where burned tyres and piles of garbage blocked streets to traffic, witnesses said.

‘Protect demonstrators’

The Sudanese Professionals Association that is spearheading the anti-government campaign said the response to Thursday’s call for protests had been “above expectations,” adding that six people had been wounded.

“We are calling on the international community to protect peaceful demonstrators as we fear the authorities will use more violence,” Mohamed Al-Asbat, a spokesman for the association told AFP by telephone from Paris.

Bashir has blamed the violence during the demonstrations on “conspirators” working against the interests of the country, without identifying them.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet on Thursday condemned Sudan’s “repressive response” to the anti-government demonstrations.

“I am very concerned about reports of excessive use of force, including live ammunition, by Sudanese state security forces during large-scale demonstrations in various parts of the country since 19 December,” she said in a statement.

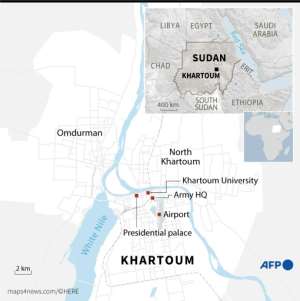

Map of Khartoum in Sudan.. By Vincent LEFAI (AFP)

Map of Khartoum in Sudan.. By Vincent LEFAI (AFP)“A repressive response can only worsen grievances,” she warned, calling on Sudan’s government to protect the protesters’ right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly, regardless of their political affiliations.

Ahead of the protests, an AFP journalist saw security personnel, many in plainclothes, stationed across the downtown area of Khartoum and along the expected route of Thursday’s march.

Several army vehicles mounted with machineguns were stationed outside the palace.

Anger over bread price

Earlier, little traffic was on the streets at what is usually the height of the morning rush hour.

The Sudanese Professionals Association, an umbrella group of unions representing doctors, teachers and engineers among others, has stepped into the vacuum created by the arrest of many opposition leaders.

More than 1,000 people including protesters, journalists, opposition leaders and activists have been arrested in a sweeping crackdown by security agents since the protests erupted.

Despite the crackdown, the movement has grown to become the biggest threat to Bashir’s rule since he took power in an Islamist-backed military coup in 1989.

The protesters accuse Bashir’s government of mismanagement of key sectors of the economy and of pouring funds into a military response Sudan can ill afford to rebellions in the western region of Darfur and in areas near the border with South Sudan.

Despite a crackdown, the protests that began over the Sudanese government’s decision to triple the price of bread have grown to become the biggest threat to President Omar al-Bashir since he took power in an Islamist-backed coup in 1989. By STRINGER (AFP/File)

Despite a crackdown, the protests that began over the Sudanese government’s decision to triple the price of bread have grown to become the biggest threat to President Omar al-Bashir since he took power in an Islamist-backed coup in 1989. By STRINGER (AFP/File)Sudan has suffered from a chronic shortage of foreign currency since the south broke away in 2011, taking with it the lion’s share of oil revenues.

That has triggered soaring inflation that has seen the cost of food and medicines more than double, and frequent shortages in major cities, including Khartoum.

A defiant Bashir has dismissed calls for his resignation but acknowledged the country faces economic problems for which a slew of reforms were being planned.